“All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.“

~ Leo Tolstoy, Anna Karenina, 1898

By Nina Heyn — Your Culture Scout

Most really good artists would not paint a family—theirs or somebody else’s—just as a record of people’s faces. They would use the theme to say something important about their sitters or to explore some art problem on the occasion of grouping several models in one setting. A case in point is the composition called Family Gathering by the French artist Fredéric Bazille (1841–1870), who painted his family on a terrace of their house in the south of France. It is a tender portrait of his relatives, but he also made sure their internal relationships and different characters are evident in their body language and expressions.

Bazille came from a well-off family, and he used his affluence to help a fellow artist named Claude Monet (1840–1926). Both of them were 26 years old when Monet tried to exhibit his large canvas Women in the Garden, but his impressionist style was soundly rejected by the jurors of the Salon in 1867. One of the Salon judges declared: “Too many young people want nothing more than to strive in this abominable direction. It’s high time to protect them and to save art.”

Bazille then purchased the painting to support his friend. He was also in artistic dialogue with this work when he painted his own take on showing people en plein air. His Family Gathering canvas is a beautiful composition of blues, beiges, and greens that takes advantage of the harsh afternoon sun of Provence to accentuate contrasts of light and to sharpen the features of his models. In this approach, he differs from Monet’s “impressionist” treatment of people’s faces; Bazille’s have very individualized expressions (after all, he knew his family well). Interestingly enough, Monet’s Women in the Garden is also sort of a family painting because his wife posed for all three figures on the left.

Monet went on to become one of the most prolific and influential artists in history. Bazille, despite his obvious talent at a young age, never had a chance—he died in the Franco-Prussian war in 1870 when he was barely 29 years old. Family Gathering remains one of his best-known works, which feels very modern despite being painted 150 years ago. Bazille’s bourgeois family portrait looks almost like contemporary photos of the British royal family—all of them solemn and posing together … and yet looking quite apart from each other.

A ROYAL FAMILY

Speaking of royal families…. One of the types of families most likely to be portrayed in any place and any era is a royal one. From antiquity onward, ruling families would be commemorated in sculptures, mosaics, and frescoes, or later in paintings and photography. By the 19th century, creating royal portraits on a regular basis had become a firmly established custom at all the courts of Europe, but at the same time, some cracks in the stiff convention of formal, commemorative portraiture had started to appear. The huge canvas Charles IV of Spain and His Family, painted in 1800 by Francisco de Goya (1746–1828), is one of the most famous masterpieces—a must-see at the Prado National Museum. For 21st-century viewers, however, Goya’s other, darker works like Los Caprichos, his Black Paintings series, or the dramatic The Third of May, perhaps speak to us more forcefully than this formal portrait of the royal family. We also probably view it much more critically than the royal family who commissioned it.

This portrait is one of the most iconic royal portraits ever painted. One of the reasons is that for a long time now, this picture has been famous as an example of Goya’s subtle mockery, something also pointed out by critics. Nineteenth-century French writer Theophile Gautier bitingly named this painting a “portrait of the owner of the corner grocery store and his wife.” Indeed, their faces are so ordinary. Modern viewers can easily spot the hard line of the queen’s mouth, the dull stare of the king, and the overall vacuous expressions of the royals, standing stiffly in formal poses. However, all Goya did was apply his talent to a convention for official portraits that would have required unsmiling, stiff, “dignified” poses. If he had some critical intention in mind in presenting the royal family members in all their conceit and lack of grace, his patrons did not notice it. This portrait was an official commission, created at numerous sittings and in preparatory oil sketches, and at its completion the king approved it for palace display. This royal family must not have detected any sarcasm here, even though subsequent generations would see this picture as proof of Goya’s disillusionment with the Spanish court and royalty in general, or at least as evidence of the extent to which his dispassionate artist’s eye would see any subject for what it was.

British and French painters active in the 1820s were much influenced by political changes in their countries. In France, the nation underwent traumatic reversals of power in 1815 with the collapse of the Napoleonic empire. In England, royal power had been steadily diminishing since the 1649 execution of King Charles I. All of this meant that while artists would often reach to literature and earlier periods of history when they created historical paintings, they would not necessarily paint pictures that were as obsequious or at least as serious as in previous centuries. Although most visual criticism was expressed in broadsheets, satirical magazines, newspaper illustrations, and other ephemera suitable for political propaganda, irreverence crept into fine art as well.

English artist Richard Parkes Bonington (1802–1828) was particularly irreverent when he illustrated an apocryphal story about Henri IV, the King of France who ruled from 1589 to 1610. Granted, Bonington was English and he was painting a foreign king, but the very idea that a monarch could be shown with such levity was unusual. King Henri IV, raised a Protestant, converted to Catholicism to keep the throne (famously declaring that “Paris is worth a mass”). His reign was characterized by religious tolerance, public works on a large scale, and promotion of education and the arts. The scene depicted by Bonington presents this king as a benign pater familias who is happy to get down on the floor to play with children, while a miffed Spanish ambassador looks on disapprovingly. While the scene is unlikely to have taken place in real life, the picture conveys both the universal approval that Henri IV enjoyed in history (he was dubbed in France “the good King Henry”) as well as a new attitude in art that treated royal subjects less reverently. There are numerous other historical paintings featuring Henri IV—including works by Rubens and Ingres—but this more intimate scene of a happy royal family has enduring charm.

A PEASANT FAMILY

No royal ever went without having his likeness immortalized in art, but on the other end of the social ladder, most peasants have faded anonymously into the dustbin of history. Peasant families did appear in some paintings in the Middle Ages—most memorably in works by painters from the prolific Breughel family—and also in numerous Renaissance and Baroque works depicting the popular theme of the adoration of the shepherds. Later on, however, some artists turned their eye toward people of this humblest class to portray them as they actually looked.

A Peasant Family in an Interior is a carefully planned composition painted by one of the Le Nain brothers. These three French artists and siblings of the 17th century painted similar subjects, and some of their works cannot be attributed with certainty to any of them individually. Here, a family of humble farmers is carefully posed and shown in the style of classic portraiture. Despite their plain, dun-colored clothes and a setting featuring a stamped-earth floor, this is not a view of a peasant household, with people having dinner in their hut. The only thing being served is wine, in an expensive crystal glass, no less, as well a single loaf of bread. Images of bread and wine in portraiture would have had obvious religious connotations during the Counter-Reformation, so even if the models were real peasants, the painting is less about their daily life and more about the contemplation of people’s relationship to religion. For Le Nain, these “salt of the earth” people clearly represented the most direct and noble example of Christian humility, but we do not learn much here about the actual French peasants of the era.

If we fast-forward to the late 19th century, after art had turned toward naturalism and social criticism, we encounter a much different way of portraying a peasant family. In 1885, Vincent van Gogh had already been painting for about two years, having abandoned his previous professions of village pastor and art dealer. He lived at the time in Nuenen, an inland, sun-deprived town in the Netherlands, where his models were local farmers, shown most famously in his dark picture The Potato Eaters. At the time, French galleries would have been full of genre scenes presenting peasant families at lively meals in colorful, fire-lit interiors, but van Gogh’s idea of a realistic genre painting was of a different kind.

In The Potato Eaters, the family members have no communication with one another, the colors are a sickly greenish-brown like the earth they till every day, and their meal of potatoes is as limited and dull as their lives must be. Their faces are distorted, almost mimicking the color and shape of potatoes themselves (van Gogh painted several studies of just the potatoes). This is neither happy nor “real-life.” Van Gogh could clearly see that the lives of those Nuenen peasants consisted of hard toil and meager meals, but his artistic path was veering away from naturalism or any social messages. A few years later, when he finally got the southern light in Arles, his canvases exploded with color, rejecting realism through the choice of hues. In 1888 van Gogh rented a small lodging in a house at Place Lamartine, which he promptly painted, creating The Yellow House. With this painting was born the deliriously bright and colorful style of one of the most creative Post-Impressionists.

The artist family painted by Polish artist Włodzimierz Tetmajer (1861–1923) is an unusual one. At the turn of the last century, several poets and painters living in the city of Kraków had yielded to a fascination with the folklore of the surrounding villages and the fashion of marrying girls from that area, and especially from a picturesque place called Bronowice. Tetmajer was one of those bourgeois artists who chose to marry outside his social class. As portrayed in this picture, his wife was a peasant, and instead of moving to the city, the couple chose to live in the village. Their children’s clothes reflect this socially mixed family—the oldest girl is dressed in traditional if festive peasant costume, but her small brother is wearing city clothes. Despite society’s warnings against such a mésalliance, and the artist’s family shunning the unacceptable bride, Tetmajer’s marriage turned out to be happy and harmonious.

Incidentally, that village of Bronowice—discovered as a haven by Tetmajer and the rest of the artistic community—not only has been long incorporated into the city of Kraków, but was deemed, in the latest poll in the summer of 2022, one of the most livable (and suitably expensive) parts of the city.

DAUGHTERS

When the Renaissance artist Sofonisba Anguissola (1535–1625) started painting, her first obvious models were the members of her family. She was taught art by her father, and, staying at home, she had to turn toward her immediate surroundings to practice portraiture. In The Chess Game, she portrayed her three sisters Minerva, Europa, and Lucia, watched over by their nanny while they are busy playing chess. This is hardly a naturalistic scene though. The girls are dressed in gold-threaded festive silks and pearl jewelry, and there is a mountain lake landscape behind them, as if they were at a villa at Lake Como rather than in a house in the flatlands of Cremona. What is also most unusual for the period is the youngest girl’s open-mouthed grin. In Renaissance art, even small children would be portrayed with their mouth closed, and often not smiling at all, especially given that the majority of such images would be formal portraits of children belonging to ruling families. The idea that commoners could have their children painted had not yet taken root. Except … when the painter was painting her own family as in this intimate picture.

If we can consider the image above as a picture of a happy family (even if “staged” to show off young Sofonisba’s professional skills), then the painting below can be interpreted as an image of a family that, if not exactly unhappy, is at least experiencing isolation.

John Singer Sargent (1856–1925) specialized in painting large-scale portraits of his wealthy and sometimes celebrity clients on both sides of the Atlantic. Toward the end of his life, Sargent had had enough of oil portraiture and switched to landscapes and watercolor impressions. He had little left to say artistically after decades of painting pictures that would scandalize (like his Portrait of Madame X as well as the portrait of Isabella Stewart Gardner) or impress (like his Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth)—or at least fulfill the desire of Gilded Age scions to have their wives grandly immortalized by the era’s most sought-after artist.

However, in an early period of his career, he created many memorable, large-scale portraits that remain as milestones in the history of 19th-century art. One of them is the aforementioned Portrait of Madame X (scandalizing with its implication of sexuality in a society lady); another—a unique image of a flamenco dancer called El Jaleo—graces a special room built for it by Isabella Stewart Gardner in her museum, and yet another one is The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit. Painted in 1882, it was a commissioned picture of four sisters—in itself a mundane subject—but the artist did not provide a traditional portrait with four clearly visible faces. The toddler is indeed positioned in the center, sitting on a carpet with her doll and calmly gazing forward, but the other three sisters’ body language is psychologically more complex. One of the girls is standing stiffly like at a school roll call, with hands behind her back the way students would have been required to do in class in those times. She was told to pose, so she is doing so, but she just stares. The two older ones are complying even less. They are way in the back in the shadows; one of them is still semi-posing, facing toward the painter, but the oldest one has already rebelled—she is leaning against the giant Japanese vase, hands crossed and certainly showing no intention to pose en face. The sisters may all be wearing childish pinafores, but their minds are already turned toward teenagehood. You could call this image “four ages of a child,” to paraphrase the titles of Old Master paintings.

Sargent was perfectly capable of creating a conventional family portrait. He did so with his portrait of The Sitwell Family, where he included all the elements important to the client—family heirlooms, nice children, and a “presentable” Victorian household—but this painting came later. In his early period, he was much freer with his brush and compositional ambitions.

Perhaps the Boits were a happy family, but what Sargent painted here is definitely not happy. The four sisters are all separate and disengaged, shown dwarfed by a richly appointed but cold and dark room. Even the smallest child is sitting alone. This is a modern portrait of alienation, even if the insights of 20th-century psychology were still around the corner in 1882 when the artist created it.

FATHER AND SON

As we can see from a preparatory drawing that Paolo Veronese did for a portrait of Count da Porto, the count’s son Adriano was supposed to hold his father’s hand but turn his body toward him and tilt his head in a pose often found in typical religious paintings. What Veronese finally painted is completely different. The count is still standing in a graceful contrapposto pose of antique sculptures, but his son is now peeking outward. He is protected by his father’s large hand, which he grabs with both hands as small children often do. This sense of safety allows him to look outward with a curious, engaged smile, instead of having an admiring but conventional tilt of his head. This is no longer an antique grandstanding pose—this is a portrait of a loving relationship between father and son.

Time has separated the father-and-son painting, now at the Uffizi gallery in Florence, from a companion portrait of the count’s wife and their daughter Deidamia. In this picture, the girl is almost hiding behind her mother’s skirts. Her body language is slightly more timid than that of little Adriano. This second part of the family “set” can now be seen at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, to be reunited only in the pages of stories like this one.

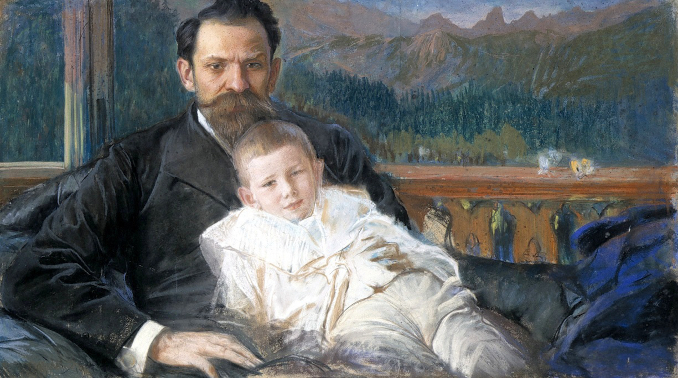

Artist Leon Wyczółkowski (1852–1936) was valued in his native Poland for his landscapes of Ukrainian fields and views of mountain lakes, but he would make a living out of painting portraits.

When he painted Stefan Żeromski in 1904, his model was one of the most popular writers of the turn of the century, well-known for his socially progressive novels and short stories. Here, he is portrayed tenderly holding his son Adam. The unusual horizontal format of the canvas allowed Wyczółkowski to paint a panorama of the Tatra mountains—a favorite vacation spot for artists and writers of the period. The clear mountain air was also considered a must for people with lung problems, and this is why the writer and his son are sitting on a terrace of a mountain house—both of them had been fighting tuberculosis. The father contracted it as a young man when living in extremely poor conditions that were later to become the setting of his socially accusatory novels. When the writer’s beloved son succumbed to the illness at age 19, Żeromski was devastated. Although this painting is from much happier times, when little Adam was just five years old, his father already has a worried frown on his face.

MONET AGAIN

We started this overview of families on canvas with a story about Fréderic Bazille supporting his friend Monet in lean times, and we can close with another story about Monet, again in the company of painters. When Edouard Manet (1832–1883), in 1874, rented a house in Gennevilliers to escape the Paris summer heat, his neighbors across the Seine were Claude Monet with his wife Camille and their son Jean. Struggling financially, the Monets for several years rented a house in Argenteuil, a place about 12 km from Paris and still a green countryside in those days. One summer afternoon, Manet visited the Monets. His portrait of the Monet family is charmingly mundane—the artist is gardening, while Camille flutters her fan and poses with her little one sprawled against her. The fun fact is that it was not only Manet who paid a visit that day. Pierre-Auguste Renoir liked to escape the summer heat, too, and visited Monet often. When he arrived that day just as Manet was embarking on the action, he borrowed brushes and painted his own version of the same scene in his free-wheeling, truly Impressionist Portrait of Madame Monet and Her Son. Camille and little Jean Monet are in the same pose in both paintings so this must have been captured at literally the same moment.

Rich or poor, happy or unhappy, some families have had the luck of being immortalized in some of the most enduring and original works of art.